This article has been archived from voces-magicae.com

The pronunciation of the divine names, nomina barbara, or voce magicae of western ritual magic can be a hotly debated subject. Many will argue that proper pronunciation of these magical formulae is not critical and that it is the intent behind the word that empowers the rite. Indeed, the power of intent is indisputable; however, there is also the essential vibrational quality of sound that I believe is as important as the intent, if not more.

Frequencies of sound are literally waves of vibrating energy and thus can have a very tangible physical, mental, and magical effect. In rituals and ceremonies throughout the world, sound is used as a transformational force to alter consciousness and to raise ambient energy. This has been something studied extensively in shamanic ritual practices but for some reason has not received as much attention in western magical traditions.

In Techniques of Graeco-Egyptian Magic, Dr. Skinner shows that the magicians of the PGM placed a tremendous amount of importance on the sounds of magical words. As more research is done into the ‘untranslatable’ words of the PGM, the more apparent it becomes that the scribes were interested in preserving the phonetics of Egyptian and semitic ‘words of power’ over their translated meaning. As such, it would seem that the Graeco-Egyptian magicians believed that proper pronunciation of the magical formulae was instrumental to the success of the magical rite.

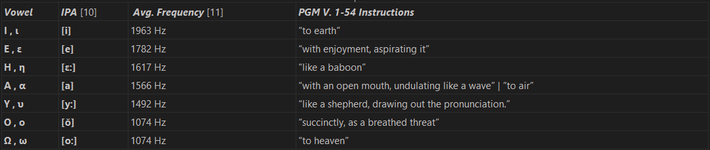

Within the magical papyri there is one spell (PGM V. 1-54) that preserves an extremely rare attempt by the scribe to teach the reader how to pronounce certain vowels. Since many of the formulae in the PGM consist of long string of vowels and vowel permutations, this passage is a unique and valuable resource for the modern practitioner of Graeco-Egyptian magic.

the “A” with an open mouth, undulating like a wave; [A, α]

the “O” succinctly, as a breathed threat. [O, ο]

the “IAÔ” to earth, to air, and to heaven. [ΙAΩ, ιαω]

the “Ê” like a baboon; [Η, η]

the “O” in the same way as above; [O, ο]

the “E” with enjoyment, aspirating it, [Ε, ε]

the “Y” like a shepherd, drawing out the pronunciation. [Υ, υ]

PGM V. 24 – 30

Both the sounds for Alpha (A/ A, α) and Omicron (O /O, o) are straight forward and correspond with the generally accepted Koine and the older Attic pronunciation.[4] We can identify these as a open-long vowel sound for Alpha (as in father) and a short vowel sound for Omicron (quicker than the o in or).

Skinner notes that since the second “O [is the] same way as above,” both Omicron and Omega (Ô/Ω,ω) should be pronounced the same. The assumption here is that the scribe mistakingly included a second Omicron instead of an Omega. However, the scribe did not make a mistake. It is clear that these vowels reference the nine-lettered magical formula that ends the incantation on line 23 of the same papyri, which indeed contains two Omicrons and the exact sequence of vowels (AOIAÔ ÊOEY). In the context of the PGM, Omega and Omicron would have most likely represented two different vowel sounds; a fact indicated in various other spells that not only speak of seven vowels, but also of seven unique sounds.

Thus, while this passage is a great reference for how some ancient Greek vowels of the PGM may have been pronounced it does not provide any insight into the vowel sounds of Omega nor Iota (I / I,ι). The scribe, does however, give us a spatial dimension in regards to these vowels in the context of the IAÔ formula, something we will return to shortly. Most scholars of ancient Greek indicate that Iota was pronounced very much like modern Greek (as ee in see) and Omega was a longer form of Omicron (as the aw in saw, in Koine Greek it was more rounded as in or).

This brings us to Eta (H, η) which the scribe says should be pronounced like a baboon. This is a long guttural and shrill ‘eh’ sound (as if holding the a in day). If, like me, you don’t happen to live in a area with a healthy baboon population, I suggest you do a quick search to find a video on youtube on baboon vocalizations. Epsilon (E, ε) is an aspirated shorter sounding ‘eh’ (as in get), a sound that can be created by following the scribes instructions and quickly aspirating ‘eh’ while smiling.

Lastly, the scribe completely baffles us in stating that Upsilon (Υ, υ) should be pronounced “like a shepherd.” Perhaps, this is one of those sounds that may have been common in the pastoral lands of the hellenic world, but today has very little meaning. Among other sounds the scribe may be referencing the sound of a panpipe or a shepherd’s flute, or perhaps even the deep bark of Molussus shepherd dog. In this context, perhaps it is best to assume that the scribe was giving more of an indication on how to draw out the sound of the vowel than the actual sound. Unlike modern Greek where Upsilon is pronounced exactly like Iota, it is believed that the sound in classical and hellenic times was more similar to the French ‘u‘ (as ou in you but tending towards the sound ‘ee-you’).

Drawing from these base vowel sounds we can start to examine their vibration qualities . This is accomplished by ordering the seven vowels according to their average frequency and pitch.

Frequency is a measure of vibration, thus this also correlates with how we experience the sound physically. Higher frequency and therefore higher pitched sounds resonate in our heads while deep base tones resonate in our basal and sacral region.

There is an apparent inversion when comparing the resonant pitch of the vowels to how the scribe indicates that the IAÔ formula should be spoken. The ‘natural’ directionality based on where the vowels physically resonate, would be Iota – Above and Omega – Below. However, the practitioner is instructed to employ the complete opposite directionality by vibrating the high-frequency Iota vowel below, and the low-frequency Omega above.

This inversion, I believe is an intended magical technique. It is analogous to the use of countermovement in other rituals of the PGM as a means to draw and center power from the unification and balance of two antipodal poles. Vibrating the IAÔ formula “to earth, to air, and to heaven” has the effect of reflecting the natural tonal frequency of sound. It is as if the magician is directing the power of the heavens downward while elevating earth energy up. The intersection and thus point of tension and balance of these two polarities is the body of the practitioner; and more precisely the harmonic breath of Alpha.

While it may be impossible to fully reconstruct the sounds of these ancient formulae, I believe that there is still much more practical knowledge we can learn by making our best attempts to pronounce the words a precisely as possible. Not only do we uncover additional levels of meaning when we examine the sounds, but we are also tapping into the specific spiritual-acoustic technology used by the Graeco-Egyptian magicians of the PGM.

Written by Leonardo.

December 26, 2014

Last edited by a moderator: